Theoretical Impact of the Pandemic, Remote Work Policies, Changing Employee Preferences on Wages, and Long-Term Employment Rates

- Alexander Mitchell

- Jun 7, 2024

- 6 min read

Updated: Feb 9

Introduction

The Covid Pandemic’s impact on preferences and labour market dynamics is analysed using two models: the Shapiro-Stiglitz and the Searching & Matching models. These models shed light on the dynamics within the labour market, wage setting, and long-term unemployment using key parameters such as separation and job finding rates, discount rates and bargaining power, to name a few.

Whilst many industries shifted online in response to the Pandemic, such as Engineering Services (consulting, management, design, etc.). Primary sectors such as Health & Social Care (hospitals, rapid response, carers, etc.) were unable to operate remotely to due to the nature of their operation, and as a result many workers’ preferences changed in response to these new working conditions.

Shapiro-Stiglitz

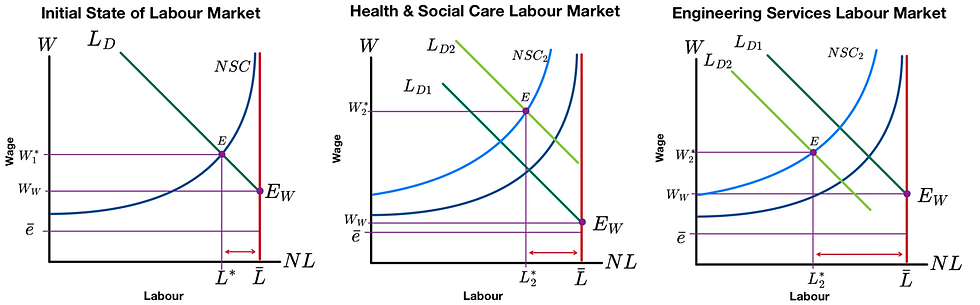

The initial change in this model is in labour demand, with distinct shifts in the two industries. Health & Social Care (HSC) experienced a significant surge in demand as the existing workforce could not keep up with the sudden surge in workload (positive productivity shock). While Engineering Services (ES) likely experienced a sudden negative productivity shock with the shift to remote working likely making work more difficult, whilst this may have been a short-run shock, labour demand still reduced.

These changes could significantly alter both industries in the long term, with potentially greater implications for the HSC industry due to lasting health impacts from the Pandemic, ES would still experience effects due to the introduction of unfamiliar collaborative software packages which may be difficult to learn (further impacting productivity).

By using the Non-Shirking Constraint (NSC) curve component of the Shapiro-Stiglitz model, the equation can be used to express how changes in relevant parameters can affect the wage that prevents shirking from workers:

The separation rate, λ, underwent very different shifts across industries. Given the Pandemic conditions, the HSC industry likely experienced a significant decrease in this value, considering that these employees played a key support role. This reduced separation rate initially lowered the NSC curve as these workers are less likely to separate due to exogenous reasons (such as increased job requirements), initially decreasing the non-shirking wage.

Conversely, the ES industry likely experienced a substantial increase in separation rates due to uncertainty surrounding sector, expressed as procurement slowdowns and hence potential redundancies, assuming no Job-Retention Scheme was in place. This increased separation rate increases the NSC curve (figure 1c), as these workers are more likely to separate due to exogenous reasons (such as uncertain business conditions), increasing the non-shirking wage. Likely compounded with other elements of the NSC equation is likely to alter the NSC curve for the ES industry.

The transition to remote/hybrid work, primarily observed in the ES industry, rather than HSC roles, led to variations in the likelihood of being caught when shirking, q. As ES workers shifted online, managers faced greater difficulties in monitoring performance, especially if the employment contract lacked precise details of requirements and job expectations. It is to be assumed that this decrease in combined with the newly established preference for online working is likely to increase the NSC curve in the long run, increasing the wage.

In both the HSC and ES industries, a common shift is anticipated: an increase in the (future) discount rate, r. This increase likely comes from shared concerns amongst workers regarding mortality risks due to Pandemic conditions. Additionally, the prevailing uncertainty is likely to encourage employees to display more present-bias behaviours and shifted priorities. Consequently, these new attitudes and preferences would increase the NSC curves to discourage employee shirking, thereby further impacting the long run wages (figures 1b and 2c). This increase in the discount rate is likely to be able to offset the impact of a decreased in the HSC industry, allowing for the NSC curve to increase (figure 1b).

Search and Matching

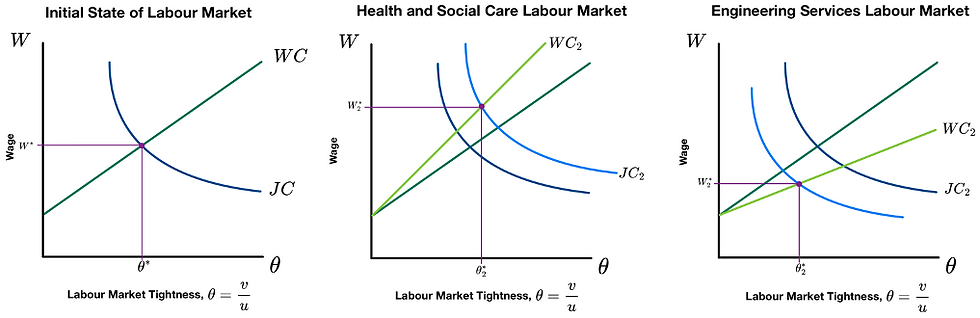

The Search and Matching model also explores changes in the separation rate (s) and discount rate (r), providing analysis similar to that observed in the Shapiro-Stiglitz model, mostly impacting the Job Creation curve. Instead, the Search and Matching analysis will examine other parameters, such as the individual worker bargaining power (β) and labour productivity (y), and then the impact on the Beveridge curves.

By using two of the main equations, the relationship between the parameters can further explain the model:

The Wage Curve (WC):

The Job Creation Curve (JC)

The bargaining power, β, experienced different shifts between the HSC and ES workers. Under the conditions of the pandemic, HSC workers encountered an unprecedented increase in demand, strengthening bargaining power. thus driving wages upwards, as depicted in Figure 2b. This increase of the wage is also likely to increase labour market tightness (θ) within the HSC industry as the new nominal wage begins to push rightwards.

Conversely, ES workers are expected to experience a substantial decrease in bargaining power, particularly in the absence of unions. Firms within this sector are likely to make some workers redundant as they expect further uncertainty. This reduced bargaining power is likely to drive down wages, as seen in Figure 2c. This decrease is also likely to introduce slack into the labour market, as new workers are willing to accept a lower wage as they have less leverage, leading to a long run decrease in wages and unemployment.

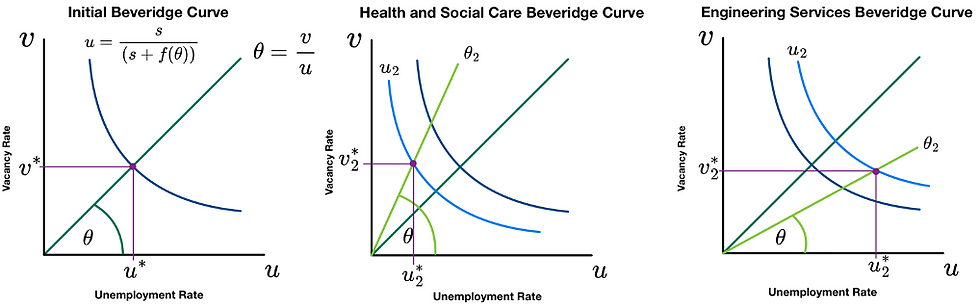

The Search and Matching model also provides an additional element, the Beveridge curve, which utilises steady-state unemployment (u_ss) and labour market tightness (θ) to describe the vacancy rate (v) and unemployment rate (u).

Steady-State Unemployment:

Labour Market Tightness:

Due the Pandemic and subsequent health-related shocks, the HSC industry is likely to have experienced a surge in demand for services, prompting health boards to generate more vacancies where possible. This increase in vacancies would have stimulated a higher job-finding rate, leading to a decline in the unemployment rate (figure 3b). Workers who were either unemployed or joining the industry would have had more options available to them, explaining the reduced unemployment rate.

Conversely, the ES industry is likely to have reduced the vacancies due to procurement slowdowns and general uncertainty. This decrease in vacancies would have restricted the job finding rate, pushing the unemployment rate up (figure 3c). Particularly as more workers were made redundant or entered this industry leaving education.

Furthermore, the separation rate (s) also has an impact on the steady-state unemployment curve. Similar to the Shapiro-Stiglitz model, HSC workers were less likely to be made redundant or leave their job. This decreased separation rate continues to decrease the steady-state unemployment curve (u_ss), as depicted in figure 3b, both reducing the unemployment rate and increasing the wage (as seen in figure 2b) through the labour market tightness function.

Conversely, the ES industry, again similar to the Shapiro-Stiglitz model, will have experienced an increase in the separation rate, expressed as workers being made redundant with increases in the unemployment rate (figure 3b). This increased rate increases the steady-state unemployment curve (figure 3c), both increasing the unemployment rate, and decreasing the wage (figure 2c) again through the labour market tightness function.

Wage Rigidity

An attractive feature of the Search and Matching model is the wage flexibility. However, nominal wages tend to rise or remain as they are, as firms fear that wage cuts negatively impact productivity and morale. In the case of reduced wages, disutility (e) will increase amongst workers, requiring a higher non-shirking wage.

Consequently, the Health & Social Care industry is expected to experience an increase in nominal wages, assuming government funds are available. Engineering Services are unlikely to experience wage cuts, except for new hires. However, this situation may place pressure on the reduction of costly vacancies, further increasing unemployment within the sector.

Conclusion

Through examination of the Shapiro-Stiglitz and Search & Matching models in the context of post-Pandemic labour markets, it becomes evident that both models offer valuable theoretical insights into both the Health & Social Care and Engineering Services industries that experienced the Pandemic and related shocks differently, as well as the following impacts on labour markets, wage setting, and unemployment.

Analysis shows that the Health and Social Care industry likely experienced higher nominal wages and reduced unemployment, through favourable labour market conditions. While Engineering Services likely faced stagnant nominal wages, and sharp increases in unemployment.

Comentários